Talk About Movies: “The Mission”

Talk About Movies: “The Mission”Matthew Lickona and Ernie Grimm discuss current and classic films from a Catholic perspective

The Mission Directed by Roland Joffé Starring Robert DeNiro, Jeremy Irons 1986, 126 minutes, English, color, United Kingdom Bishop's rating: A-III (adults)

Ernie:

First let me welcome and thank you, John Teresa, for standing in for Matthew, who is on a vacation/pilgrimage to Rome.

Now, to The Mission... just as he admired Saint Thomas More in his Man for All Seasons, Robert Bolt, who also wrote The Mission, clearly admired the self-sacrifice displayed by these Jesuit missionaries.And how could one not admire men who face the peril of climbing the Iguacu Falls only to face near certain death at the hands of Indians who have already killed one of their priests? But the problem is, Bolt -- who was not a believer -- didn't understand that it was a desire to save the souls of these Indians that propelled these missionaries up the falls to face death. He portrays the missions primarily as communes, and the movie lapses into a sort of apologia for communistic ideals.

John:

Thank you Ernie, it really is my pleasure. In last Sunday’s readings, Acts 2:42-47, -- Divine Mercy Sunday I might add -- didn’t we hear, “They devoted themselves to the teaching of the apostles and to the communal life, to the breaking of the bread and to the prayers.” Didn’t we also hear, “All who believed were together and had all things in common; they would sell their property and possessions and divide them among all according to each one's need.” If we read history into the film, perhaps you can make that assessment viewing with 21st century eyes, but if we view it in historical context, why wouldn’t a tribal people live in close community? That is hardly a lapse into materialism.

Ernie:

I'm not arguing against the idea that communal life was the best idea for the Guarani Indians who had always lived communally. I'm lamenting the fact that the missions/communes were portrayed as ends in themselves.

Thank you Ernie, it really is my pleasure. In last Sunday’s readings, Acts 2:42-47, -- Divine Mercy Sunday I might add -- didn’t we hear, “They devoted themselves to the teaching of the apostles and to the communal life, to the breaking of the bread and to the prayers.” Didn’t we also hear, “All who believed were together and had all things in common; they would sell their property and possessions and divide them among all according to each one's need.” If we read history into the film, perhaps you can make that assessment viewing with 21st century eyes, but if we view it in historical context, why wouldn’t a tribal people live in close community? That is hardly a lapse into materialism.

The desire to save souls was certainly conveyed when Father Gabriel took the cross of the martyred Jesuit, and climbed the falls. He was excoriated by Don Cabeza for asserting the primacy of the soul during the tour of great mission of San Miguel.It was conveyed later in the film when he gave the martyr priest's cross to Father Mendoza before the battle. This is a powerful film that intersects many dimensions of our faith. To limit it to an apologia for communistic ideals is too narrow an interpretation.

Ernie:

I'm not arguing against the idea that communal life was the best idea for the Guarani Indians who had always lived communally. I'm lamenting the fact that the missions/communes were portrayed as ends in themselves.

We get precious little of religious life, liturgy, or even prayer in this movie. Instead, we get shots of planting crops, building shelters, picking bananas, making violins. There is some singing of the Ave Maria, but it's portrayed more as art than as worship. Just about the only time we see anybody in prayer is when the cardinal from Rome is using prayer as an excuse for indecision.Near the end, we do see Father Gabriel leading the Indians of San Carlos in a Eucharistic procession. But the cynic in me can't help but notice that they're following the Eucharist -- which the writer of this screenplay thinks is nothing more than bread -- unto their deaths. And at the end, the cardinal writes to the pope that the priests who died at San Carlos still live while he (the cardinal) is dead. But it's not because they're in heaven, but because "they live on in the memory of the living." The only way the Marxist message in this movie could have been clearer is if he'd said, "There is no heaven, only communal paradise on earth."

John:

I don’t think you are a cynic. I think you are skeptical, as well you should be about Bolt’s intentions. However, let me try to assuage your skepticism.

I don’t think you are a cynic. I think you are skeptical, as well you should be about Bolt’s intentions. However, let me try to assuage your skepticism.

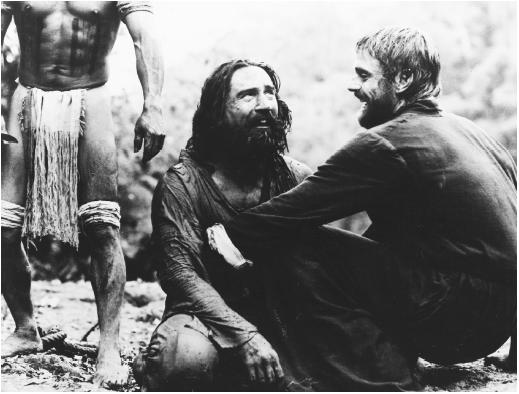

This is not a movie specifically about religious life. It is also about pride, sin, justice, injustice, politics, economics, genocide, transformational forgiveness, mercy, love, and redemption. Like you, I was troubled by the cardinal’s ending lines. I was also troubled by Father Gabriel’s defense of the Guarani’s infanticide.During the tribunal he gave the root cause, but failed to comment on this act’s moral and spiritual repercussions for both the Guarani and the colonists. But there were relatively few scenes about the missions and communal life. The majority of the film was about Father Mendoza and his transformation from slave trader and mercenary to priest. The pride that killed his brother and left no room for God’s redemption was slowly drained away as he dragged his sin behind him in a torturous assent to the Guarani. Atop the falls, exhausted, covered in the filth of his sin, Mendoza encounters them. The same man who apologetically retrieved Father Gabriel’s broken oboe from the water, grabs the knife that Mendoza used to kill his brother, and holds it to his throat. Proud to his last moment Mendoza awaits just revenge without fear, but instead the man cuts the rope freeing him. The knife that was an instrument of murder, and could have been an instrument of justice, is instead an instrument of mercy. This act breaks Mendoza’s pride, and frees him from his past as his armor slips beneath the water. He weeps in grief and joy as he can now accept God’s divine mercy. A few materialist lines might cloud the film for some, but despite Bolt’s non-belief this is a profoundly Christian film.

Link (here)

No comments:

Post a Comment