THE INDIGENOUS & THE FOREIGN

THE INDIGENOUS & THE FOREIGNThe Jesuit Presence in 17th Century Ethiopia

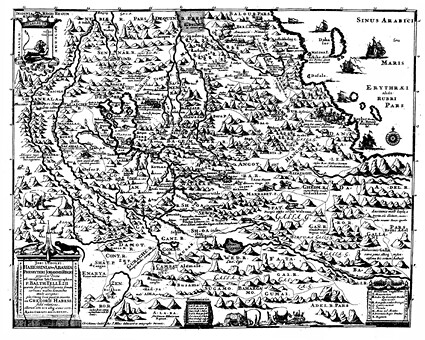

In the rural plateaux of northern Ethiopia, one can still find scattered ruins of monumental buildings alien to the country's ancient architectural tradition. This little-known and rarely studied architectural heritage bears silent witness to a fascinating if equivocal cultural encounter that took place in the 16th-17th centuries between Orthodox Ethiopians and Catholic Europeans. The Indigenous and the Foreign explores the enduring impact of the encounter on the religious, political and artistic life of Christian Ethiopia, one not readily acknowledged, not least because the public conversion of the early 17th-century King Susenyos to Catholicism resulted in a bloody civil war enveloped in religious intolerance. Included in this presentation are photographs showing the surviving architecture of a number of religious and stately buildings of early 17th-century Ethiopia, a period when a mission of Jesuits from Goa, in Western India, was most active at the Ethiopian Christian king's Court. This important heritage, known as pre-Gondarine, is scarcely known outside of Ethiopia. The photographic exhibition is complemented by a show of Jesuit books belonging to the Biblioteca Pública de Braga, and manuscripts from the Archive of the Conde da Barca, which are now in possession of the Arquivo Distrital de Braga.

The catalogue includes a number of images from illustrated Ethiopian manuscripts and texts from the period, kindly lent by The British Library and the SOAS Archives, with further examples of Ethiopian art from Private Collections, which were in display when the present exhibition was shown at the Brunei Gallery (SOAS - University of London), from July to September 2004, on the occasion of the launching of the book The Indigenous and the Foreign in Christian Ethiopian Art (eds. I. Boavida e M. J. Ramos).

The Jesuits in 16/17th-Century Ethiopia The Christian kingdom that controlled the Ethiopian high plateaux suffered a series of very deep political, economic, military and religious crises in the period between the late 15th century and the expulsion of the Jesuit missionaries in 1633. The Somali and Afari armies led by Ahmad ibn Ibrahim, called the Gragñ (or “left-handed”) seriously threatened the very existence of the Christian state from 1529 to 1543, when they were finally defeated by the Abyssinians with the help of a small Portuguese expeditionary force sent from Goa, India. Subsequently, parties of Borana and Barentuma Oromo pastoralists began raiding deeper and deeper into Abyssinian territory and, by the end of the 16th century, many had settled in Gojam and Shoa and had become the main adversaries of royal power in Abyssinia. The Portuguese military collaboration with the Christian Ethiopians served their own strategic interests in their regional rivalry with the Ottoman Turks for control of the trade routes in the Red Sea and the north-western sector of the Indian Ocean. But the Portuguese rulers, together with the Pope in Rome and the head of the Company of Jesus, had the additional intention of establishing a mission in Ethiopia to encourage the population to switch from their Orthodox faith to Catholicism – an intention that made sense in the light of the Counter-Reformation concerns in Southern Europe. A Jesuit mission led by Father Andrés de Oviedo first entered the country in 1557, only to find that the conversion project was too utopian. They began visiting the royal court, where they participated in a number of theological discussions with the Orthodox clergy. But they were eventually persecuted and expelled to Tigray where, in May Gwagwa, they preached and gave support to the Portuguese community that had stayed in Ethiopia in the wake of the Gragñ wars. As the years passed and the Portuguese either dwindled in numbers or converted to Orthodoxy, the mission became almost extinct. By the end of the century, when Philip II, the Emperor of Spain, inherited the Portuguese royal crown, he decided to revive the Jesuit mission in Ethiopia. A new priest, Father Pedro Páez , was sent from Goa. Once in Ethiopia, he forced his way into the royal court. Other priests joined him and together they gradually gained the favour of the new Ethiopian King Susneyos and, very importantly, converted his brother the Ras Sela Krestos to Catholicism. In 1621, Susneyos publicly announced his adherence to the Latin faith, a strategy to reinforce his political power and his independence from the influential Orthodox clergy. A consequence of the public conversion of the king was the arrival of a growing number of Jesuit priests intent on rapidly introducing Catholic reforms into Ethiopia. In 1626, the Catholic Patriarch Afonso Mendes imposed a number of changes on the ancestral religious practices of the Ethiopians. Social unrest and civil war followed and Susneyos was forced to resign. His son Fasiladas, who succeeded him, rejected Catholicism upon his accession to the throne and, in 1633, expelled or killed all Jesuit missionaries.

Link to original article (here)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Due to a high volume of spamming I have had to enable comment moderation. It may take a day to see your comment published. Respectful and thoughtful comments welcome