Holy Apostles Jesuit Chapel, Norwich

I travelled much about Norfolk about 1890, and was surprised to find many traces of the old Jesuit missions of the 17th and 18th centuries in pictures and rosaries still preserved by the descendants of those who first received them. I was a pupil of two different Church of England clergymen when I was a boy, and the sexton to one of them had three pictures, on glass, of Our Lady of Sorrows, The Sacred Heart, and the Immaculate Conception, which, he told me, were 'from the Romans when they came about these parts'.

- Frederick Hibgame, quoted in A Great Gothic Fane: a Retrospective of Catholicity in Norwich, 1913

The Jesuits, or, more accurately, the Priests of the Society of Jesus, were missionary Priests, the Vatican's answer to the prohibition of Catholicism in England by Elizabeth I and her successors. The attempted destruction of Catholicism in 16th century England was two-pronged. Firstly, the practice of the faith was outlawed, by forbidding Catholics from congregating, and fining them for failing to attend Anglican services. Secondly, the very act of being a Catholic Priest within the realm was declared treasonable, to be punished by a long, painful and public death: hanging, drawing and quartering. This was the England to which the Jesuits, Englishmen trained and ordained on the continent, were returning to minister.

Being hung, drawn and quartered was intended to be both shameful and disgusting. The victim was effectively butchered while still alive. Yet this fate awaited many of these prayerful Christian emissaries, and several Norfolk-born Jesuit Priests suffered it during the later years of the 16th century. First, the victim would be suspended, almost naked, by the neck until he began to lose consciousness. Then, he would be cut down and revived. His genitals were removed with a knife and displayed to the crowd before being thrown into a fire; the celibacy of Catholic Priests was a particular cause for scorn. Next, his bowels would be wound out on a windlass in front of his eyes, and then his arms and legs were hacked off and burnt. If he was lucky, he would be dead before he was finally beheaded. Hundreds of Priests were willing to risk this fate to keep the Old Faith alive in England, which tells us something about the strength of their faith.

Not surprisingly, Catholics had become a beleagured minority in England by the start of the 17th century. The new theological battleground was between Anglicans and Puritans, in their fight for the heart and soul of the Church of England and the early modern British State. Perhaps because of this marginalisation into virtual irrelevance, it became easier for Catholics to carry on their faith, as long as they kept quiet about it. There were one or two hiccups; for example, the coup that removed James II and put WIlliam III on the throne in 1688 caused an uprise in persecution; but generally the Jesuits were able to quietly go about their work, ministering the sacraments to the faithful. By now, there were perhaps less than a thousand Catholics in the whole of Norfolk.

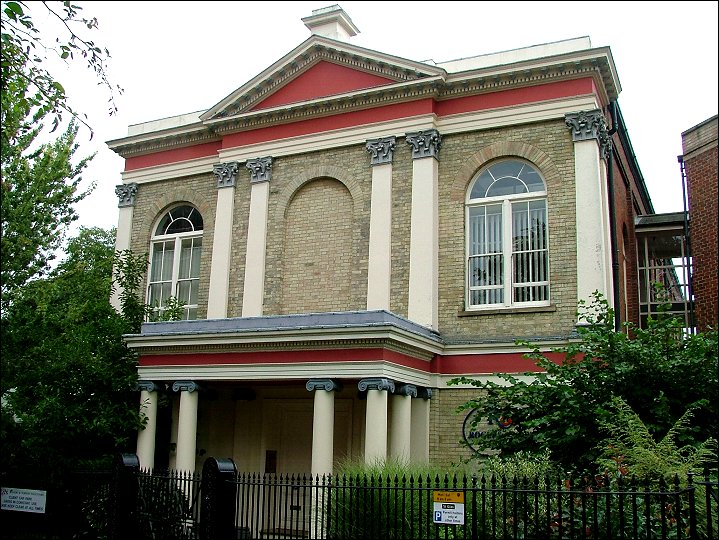

The Jesuit mission to Norwich established a centre in the Chapelfield area, and towards the end of the 18th century they built a discreet little chapel in St Swithin's, not far from the Anglican parish church. The fallout from the French Revolution, as well as public revulsion at the Gordon Riots, a pogrom in which hundreds of London Catholics were killed in in 1780, led in the 1820s to the first in a series of reform acts. For the first time, Catholics were able to organise openly, and the Jesuits in Norwich commissioned a grand, Classical chapel in fashionable Willow Lane in St Giles.

The chapel was the work of James Patience, and its grand palladian frontage was a bold move. The St Swithin's chapel had been in a little back street, and the other central Catholic church in Maddermarket was equally discreet. This chapel was commissioned at a time when Catholic worship was still technically illegal. It opened on September 29th 1829 with a high pontifical Mass. This was in the days before the 1851 Restoration of the Heirarchy had brought Bishops back to England and Wales, and so the Vicar General was brought in from the Midlands to celebrate the first Masses. An Irish Bishop preached in the afternoon.

There was a curious incident, noted in A Great Gothic Fane, that occured on the same day. Across the road from the chapel, at the top of the opposite hill, sits St Giles church, and for the whole of that Sunday its bells rang out. Perhaps it was a simple act of Anglican triumphalism, the Parish church declaring its presence; but it might just have been an act of celebration of the new Chapel, because the Anglican Bishop of Norwich, Henry Bathurst, was well-known for his intelligence and theological liberality, and had been a supporter of Catholic political claims in the House of Lords. It was his approval, or perhaps more accurately the lack of his opposition, that had led the Jesuits to purchase the land in WiIllow Lane ahead of the Reform Act that would allow them to build their chapel. Perhaps he looked with a benign eye upon these strangers in his midst who he was bound to think of as part of his flock.

Holy Apostles chapel became the main venue for the Mass in central Norwich throughout the middle years of the 19th century. Actually, there is some documentary evidence that the official dedication of the chapel was to St Peter and St Paul, but it was popularly known as the Holy Apostles chapel, probably because the Jesuit Priests that served Norwich from Stonyhurst were the Holy Apostles Mission, and the name stuck. It took its place as one of Norwich's many non-Anglican places of worship, and during the century established itself as the focus of the Catholic cause.

In 1847 the interior was richly decorated, and the windows filled with stained glass. In 1851, Norwich became a part of the new Diocese of Northampton, and was its second biggest city. The Catholic population of Norwich grew - by 1870, the Holy Apostles parish was caring for about 1200 Catholics, and was one of two central Catholic churches, the other being on Fishergate near the Anglican Cathedral. By 1880, the Jesuits were preparing to withdraw from Norwich, their mission work done. There was also talk of replacing the two chapels with something more fitting; Cambridge and Ipswich both now had large, central Catholic churches, and surely Norwich should be able to do better?

As we know, the Duke of Norfolk stepped in, and over the next thirty years he oversaw the building of the biggest, grandest Catholic church in England, St John the Baptist, the church that in 1974 would become East Anglia's own Catholic cathedral - but that is another story. As a result, however, Willow Lane chapel closed, and was converted into a Catholic school.

After the Second Vatican Council, such small schools were inadequate for the brave new world the Church found itself in, and Willow Lane school closed in 1968. In the 1980s there was a bold conversion into offices for an insurance firm. A small structure built beside the chapel houses the stairs, and internally many of the 1847 features have been retained and enhanced, with the exception of the glass, which is now in the Catholic church at Bury St Edmunds.

In the 19th century, an antiquarian observed that, for the ordinary Norfolk labourer, the idea that his country had once been Catholic was as remote as that it had once been roamed by dinosaurs. As the practising Catholic congregation in England now passes in size the practising Anglican one, it is worth remembering these little chapels, signs of a Faith that was kept when all seemed lost.

I travelled much about Norfolk about 1890, and was surprised to find many traces of the old Jesuit missions of the 17th and 18th centuries in pictures and rosaries still preserved by the descendants of those who first received them. I was a pupil of two different Church of England clergymen when I was a boy, and the sexton to one of them had three pictures, on glass, of Our Lady of Sorrows, The Sacred Heart, and the Immaculate Conception, which, he told me, were 'from the Romans when they came about these parts'.

- Frederick Hibgame, quoted in A Great Gothic Fane: a Retrospective of Catholicity in Norwich, 1913

The Jesuits, or, more accurately, the Priests of the Society of Jesus, were missionary Priests, the Vatican's answer to the prohibition of Catholicism in England by Elizabeth I and her successors. The attempted destruction of Catholicism in 16th century England was two-pronged. Firstly, the practice of the faith was outlawed, by forbidding Catholics from congregating, and fining them for failing to attend Anglican services. Secondly, the very act of being a Catholic Priest within the realm was declared treasonable, to be punished by a long, painful and public death: hanging, drawing and quartering. This was the England to which the Jesuits, Englishmen trained and ordained on the continent, were returning to minister.

Being hung, drawn and quartered was intended to be both shameful and disgusting. The victim was effectively butchered while still alive. Yet this fate awaited many of these prayerful Christian emissaries, and several Norfolk-born Jesuit Priests suffered it during the later years of the 16th century. First, the victim would be suspended, almost naked, by the neck until he began to lose consciousness. Then, he would be cut down and revived. His genitals were removed with a knife and displayed to the crowd before being thrown into a fire; the celibacy of Catholic Priests was a particular cause for scorn. Next, his bowels would be wound out on a windlass in front of his eyes, and then his arms and legs were hacked off and burnt. If he was lucky, he would be dead before he was finally beheaded. Hundreds of Priests were willing to risk this fate to keep the Old Faith alive in England, which tells us something about the strength of their faith.

Not surprisingly, Catholics had become a beleagured minority in England by the start of the 17th century. The new theological battleground was between Anglicans and Puritans, in their fight for the heart and soul of the Church of England and the early modern British State. Perhaps because of this marginalisation into virtual irrelevance, it became easier for Catholics to carry on their faith, as long as they kept quiet about it. There were one or two hiccups; for example, the coup that removed James II and put WIlliam III on the throne in 1688 caused an uprise in persecution; but generally the Jesuits were able to quietly go about their work, ministering the sacraments to the faithful. By now, there were perhaps less than a thousand Catholics in the whole of Norfolk.

The Jesuit mission to Norwich established a centre in the Chapelfield area, and towards the end of the 18th century they built a discreet little chapel in St Swithin's, not far from the Anglican parish church. The fallout from the French Revolution, as well as public revulsion at the Gordon Riots, a pogrom in which hundreds of London Catholics were killed in in 1780, led in the 1820s to the first in a series of reform acts. For the first time, Catholics were able to organise openly, and the Jesuits in Norwich commissioned a grand, Classical chapel in fashionable Willow Lane in St Giles.

The chapel was the work of James Patience, and its grand palladian frontage was a bold move. The St Swithin's chapel had been in a little back street, and the other central Catholic church in Maddermarket was equally discreet. This chapel was commissioned at a time when Catholic worship was still technically illegal. It opened on September 29th 1829 with a high pontifical Mass. This was in the days before the 1851 Restoration of the Heirarchy had brought Bishops back to England and Wales, and so the Vicar General was brought in from the Midlands to celebrate the first Masses. An Irish Bishop preached in the afternoon.

There was a curious incident, noted in A Great Gothic Fane, that occured on the same day. Across the road from the chapel, at the top of the opposite hill, sits St Giles church, and for the whole of that Sunday its bells rang out. Perhaps it was a simple act of Anglican triumphalism, the Parish church declaring its presence; but it might just have been an act of celebration of the new Chapel, because the Anglican Bishop of Norwich, Henry Bathurst, was well-known for his intelligence and theological liberality, and had been a supporter of Catholic political claims in the House of Lords. It was his approval, or perhaps more accurately the lack of his opposition, that had led the Jesuits to purchase the land in WiIllow Lane ahead of the Reform Act that would allow them to build their chapel. Perhaps he looked with a benign eye upon these strangers in his midst who he was bound to think of as part of his flock.

Holy Apostles chapel became the main venue for the Mass in central Norwich throughout the middle years of the 19th century. Actually, there is some documentary evidence that the official dedication of the chapel was to St Peter and St Paul, but it was popularly known as the Holy Apostles chapel, probably because the Jesuit Priests that served Norwich from Stonyhurst were the Holy Apostles Mission, and the name stuck. It took its place as one of Norwich's many non-Anglican places of worship, and during the century established itself as the focus of the Catholic cause.

In 1847 the interior was richly decorated, and the windows filled with stained glass. In 1851, Norwich became a part of the new Diocese of Northampton, and was its second biggest city. The Catholic population of Norwich grew - by 1870, the Holy Apostles parish was caring for about 1200 Catholics, and was one of two central Catholic churches, the other being on Fishergate near the Anglican Cathedral. By 1880, the Jesuits were preparing to withdraw from Norwich, their mission work done. There was also talk of replacing the two chapels with something more fitting; Cambridge and Ipswich both now had large, central Catholic churches, and surely Norwich should be able to do better?

As we know, the Duke of Norfolk stepped in, and over the next thirty years he oversaw the building of the biggest, grandest Catholic church in England, St John the Baptist, the church that in 1974 would become East Anglia's own Catholic cathedral - but that is another story. As a result, however, Willow Lane chapel closed, and was converted into a Catholic school.

After the Second Vatican Council, such small schools were inadequate for the brave new world the Church found itself in, and Willow Lane school closed in 1968. In the 1980s there was a bold conversion into offices for an insurance firm. A small structure built beside the chapel houses the stairs, and internally many of the 1847 features have been retained and enhanced, with the exception of the glass, which is now in the Catholic church at Bury St Edmunds.

In the 19th century, an antiquarian observed that, for the ordinary Norfolk labourer, the idea that his country had once been Catholic was as remote as that it had once been roamed by dinosaurs. As the practising Catholic congregation in England now passes in size the practising Anglican one, it is worth remembering these little chapels, signs of a Faith that was kept when all seemed lost.

Link (here)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Due to a high volume of spamming I have had to enable comment moderation. It may take a day to see your comment published. Respectful and thoughtful comments welcome